Some properties that may apply to a site-specific work:

Physically accessible, different curatorial practices, dimension of

documentation as part of work, not commodifiable in capitalist art market, (can

be) temporal, interplay with site, can address the site’s history and cultural

value when threatened, shifting meaning from art object itself to context and

interplay between object(s) and site.

“If modernist

sculpture absorbed its pedestal/base to sever its connection to or express its

indifference to the site, rendering itself more autonomous and self-referential,

and thus transportable, placeless, and nomadic, then site-specific works, as they first

emerged in the wake of Minimalism in the late 1960s and early 1970s, forced

a dramatic reversal of this modernist paradigm.” –Miwon Kwon

Gordon Matta-Clark and Creative destruction

“The notion of “anti- or non-architecture” was based on the

use of space as a conceptual element, not only from an architectural dimension,

but also in relation to social space.

The intention was to take advantage of the holes, empty space, and unused

places …”

-Lola Hinojosa

“His best-known works of the ’70s, including abandoned

warehouses and empty suburban houses that he carved up with a power saw,

offered potent commentary on both the decay of the American city and the

growing sense that the American dream was evaporating. The fleeting and

temporal nature of that work — many projects were demolished weeks after

completion — only added to his cult status after an early death in 1978, from

cancer, at 35…how cleverly he challenged the high priests of architecture who,

in Matta-Clark’s mind, inhabited a world of lofty abstractions divorced from

the physical reality of everyday life. That critique is newly resonant, when

even the most radical architectural ideas are quickly gobbled up by the

cultural mainstream and take on the slickness of advertising slogans.”

-NYT

Splitting (1974) – Performance and video

This

house was located in Englewood, New Jersey, which was a suburb developed

during white flight from the urban core, and was experiencing depopulation

after the post-war downturn at the time of the work. With Matta-Clark’s work

there was an emphasis on physical process as performance, as the artist worked

with another laborer to create the fissure by jack-hammering away at the

foundation, removing a layer of bricks, and making a clean cut through the

middle.

“Matta-Clark understood the psychic power of buildings over

people. In one notebook from 1976, he wrote that he wanted to ‘convert a place

into a state of mind’. [8] This bond between home and occupant was articulated

in the correspondence that Matta-Clark received after Splitting was opened for

viewing. A number of letters complained about what he had done, saying that he

had violated the sanctity and dignity of abandoned buildings; one even likened

it to rape. [9]

Matta-Clark felt, like the Situationists, that this dream

had been used as a political tool by the ruling classes through the provision

of convenience and dwellings, in order to contain and control the masses.”

-The Ibtauris Blog

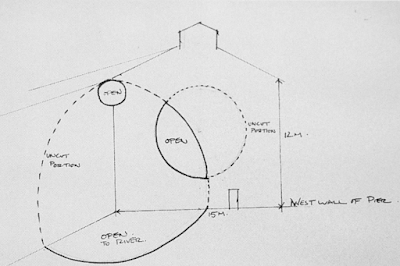

Day’s Passing/Day’s End (1975)

“During the summer of 1975, Matta-Clark made a series of

large cuts into a 600-ft long metal hangar on Pier 52 that had once belonged to

the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company. Removing sections of the floor and

ceiling, along with portions of the western and southern sides of the building,

the artist exposed the river and sky, creating a changing sculpture of light

out of a structure the city had largely abandoned.”

-Creativetime.org

“…(it was) a temporary cathedral of light. He even made a

moat inside, by removing a 10-foot-wide section of the wood floor. And with a

blowtorch he cut an enormous elliptical window out of the tin wall at the far

west end.

In the film…you see him suspended, his face brightly

reflected in the sparkly glare of the torch, cutting the ellipse, then slowly

removing it with a winch. Late afternoon sun pours around the edges, making a

kind of drawing out of blinding light. The effect resembles a lunar eclipse,

and it’s just plain magnificent.”

-NYT

The

idea was to reclaim a lost and abandoned part of deindustrialized New York City

for public enjoyment and creative expression. This was illegal and unpermitted!

Unfortunately it was immediately closed by the police, and was never open to

the public, as intended. Works like this become commodified through

documentation, for example, a 23 minute super 8 film about this work is in

MoMa’s collection.

Inigo Manglano-Ovalle - Le Baiser/The Kiss (1999)

“…is set in Mies's Farnsworth House and features a

large-scale double-sided video projection

that presents the artist as a window washer dressed in workman's jumpsuit,

carefully washing the house's large exterior windows and glass doors with a

squeegee. Inside the house, a woman stands at a DJ station spinning records,

conspicuously oblivious to the diligent window washer right outside the window.

In this work, Manglano-Ovalle pays homage to Mies's cool modernist space while

at the same time sets up a social dynamic that explores the nuances of class

structures and hierarchies.”

-Orange

County Museum of Art

Doug Aitken, Mirage (mirror house) (2017)

This work is a commentary on urban sprawl and

encroachment on the last undeveloped parts of open land, using the Coachella

Valley in California as a setting. Not surprisingly, it also serves as the

ideal backdrop for Instagram and other social media. This work is interesting

to me because, though it was ostensibly created as a statement about

commodification and consumerism, it also functions as the perfect commodity

fetish object.

“In the tradition of land-art as a reflection of the dreams

and aspirations projected onto the America West, Mirage presents a continually

changing encounter in which subject and object, inside and outside are in

constant flux. The ranch-style structure suggests a latter-day architectural

version of manifest destiny, a primary structure rendered by the artist without

function service or texture.”

-DesertX Website

“Aitken describes “Mirage” as a study of the relationship

between the architecture of the typical suburban ranch house (and its

forebears, including residential designs by Frank Lloyd Wright and others) and

the natural landscape that it both relies upon and threatens to destroy. ‘I

knew for the work to function I need a location on a hillside where there’s a

view of urban sprawl…Where the sprawl ends and the desert begins. This is not

the kind of project where you can compromise and do it wherever.’”

-LA Times, Christopher Hawthorne

“’In a lot of ways,” he explains, “the inspiration for this

as a sculpture is the architecture you don’t remember. I was interested in what

you had driven by thousands of times and you don’t even register its presence

because it’s just so much a part of the pattern.’”

-Architectural Digest

Rachel Whiteread, Cabin (2015)

Whiteread’s work deals with architecture, space, absence and

memory. She often uses casting processes, with materials like plaster,

concrete, resin and rubber, to highlight the absence of the referenced original

structure or object.

She is a British artist, and Cabin is her first major US

commission – part of the Governors Island Park revitalization efforts in New

York. The work is intended to evoke the contemplative solitude of Thoreau, but

it could also be read as a retreat fitting for the Unibomber, with views of

both the Statue of Liberty and Ground Zero.

“’It is partly my mission to make things more complicated to

look at, more of an effort and more of an experience,” she continues. “You get

on a boat and go across the water. You’ll see the Staten Island ferry, see Lady

Liberty, get a little bus or walk across the island and then you’ll come across

Cabin. It’s not a quick thing and it’s to do with expectation. The whole thing

will take a few hours and will hopefully remain with you for a few hours. I

hope people try to get some sense of what I am trying to make happen. It’s a

slow burn.’”

-The Guardian

“But she said: ‘I’m not a great fan of what I call ‘plop

art’, where you plop a piece of work down where it doesn’t bear any

relationship to anything else. Art has got extremely popular, and for many reasons that’s great. But

I think a lot of public sculpture is ill thought out and put in places that it

shouldn’t necessarily be.It becomes something then that’s invisible. People

don’t even notice it. Art is there for a reason and should be respected and

looked at and not just a side show.’

-Belfast Telegraph

Chihara Shiota, Trace of Memory (2013)

The Mattress Factory, Pittsburgh, PA

“…while some

people try to cleanse spaces or their superstitious gateways by sageing

doorways, this installation does the opposite, appealing to some kind of

liminal god to crack open time, resurface the past, and let it linger in the

present...Shiota came up with stories by drawing from the building’s

many layers of wallpaper, while imagining the lives of the house’s former

occupants. Following the deindustrialization of the US and the resulting

economic collapse around 1980, 516 Sampsonia Way sat empty for years.’”

Jenny Holzer, Truisms/Messages to The Public (1982)

Messages to The Public

was a public art project that used the Spectacolor board in Times Square for a

changing sequence of artists from 1982-1998 to display words and images. Jenny

Holzer’s contribution, part of her Truisms series, is one of the most well-known.

“"Jenny Holzer's Truisms are "truths" that

lie at the boundary of truth and our perception of truths in the post-modern

landscape. Holzer inserts her truisms into public spaces, on T-shirts, and

electronic billboards placed in museums and galleries. As a fixture in public

space, they are in jarring juxtaposition to the commodified world around us of

mass media, advertising, product marketing, and all the various

"non-truisms" that are fed to us everyday. In this sense, the Truisms

are an act of artistic mediation, in that Holzer inserts her work and ideas

into the real world where they activate critique and analysis of surrounding

cultural, economic and political conditions."”

-Zakros

“Jane Dickson, a painter, was working for Spectacolor, Inc.

as an ad designer and computer programmer when, three and a half years ago, she

first thought to use the light board to display noncommercial art. ‘I picked

that title,’ she said of Messages to the Public, ‘because I thought the

propaganda potential from this project was terrific.’ The board, she noted, was

regularly used for ‘commercial propaganda.’ Dickson sought help from the Public

Art Fund, an organization based here and dedicated to taking art out of the

galleries and placing it in the city’s streets and parks. Project director of

the Public Art Fund Jessica Cusick explained, ‘We’re trying to do art that’s

timely, has a message, is visually potent and is trying to deal with the fine

line dividing fine art and commercial art.’”

Selections from the whole

project.

Jerry Rubin, Abby Hoffman, et al (The Yippies),

Levitating the Pentagon (1967)

“…its historic and seminal merging of a creative “happening”

with political intent, the engagement of ritual towards political ends and the blatant

usurpation of corporate media techniques in service of a movement. The action’s

absurdism extended even to the process of securing a permit beforehand; the

authorities finally agreed to allow the Pentagon to be elevated three feet in

the air, down from the 300 feet that organizers had initially requested”

“No need to build a stage, it was all around us. Props would

be simple and obvious. We would hurl ourselves across the canvas of society

like streaks of splattered paint. Highly visual images would become news, and

rumor-mongers would rush to spread the excited word. … For us, protest as

theater came natural. We were already in costume. … Once we acknowledged the

universe as theater and accepted the war of symbols, the rest was easy. All it

took was a little elbow grease, a little hustle.” – Abby Hoffman

Sites:

No comments:

Post a Comment